by Dr. Phil on December 23, 2014

by Dr. Phil on July 13, 2014

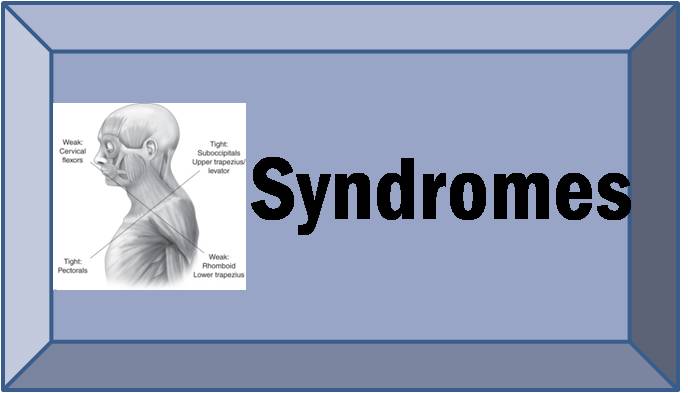

While Vladimir Janda was the first to recognize Upper Crossed Syndrome (UCS) and Lower Crossed Syndrome (LCS), few studies have validated the specific pattern of muscle imbalance and postural abnormalities associated with these common muscle imbalance syndromes.

Janda’s Upper Crossed Syndrome

Matthias Treff, a Masters student in Engineering at Virginia Polytechnic recently wrote his thesis, “An investigation of musculoskeletal imbalances in the thoracic and cervical regions, with respect to an improved diagnostic approach for Upper Crossed Syndrome.” The purpose of his research was to determine if differences existed in cervical range of motion as well as cervical and shoulder muscle performance between a group of patients with UCS and subjects without symptoms. The study was a case-control design of 17 subjects with UCS (15 females and 2 males) and 17 matched healthy subjects. They were tested for range of motion and isometric strength and endurance of the neck and shoulder muscles using an isokinetic dynamometer. Compared to healthy subjects, statistically significant decreases in active neck range of motion in bending and rotation were found in the UCS patients, but there was no difference in flexion or extension range of motion. Significant weakness in isometric neck flexion and extension was found in the UCS patients compared to healthy subjects, as well as significant isometric weakness of shoulder external rotation and adduction. Strength ratios of shoulder internal/external rotation and abduction/adduction were also significantly lower in the UCS patients. There was no significant difference in muscular endurance between the UCS patients and healthy controls. The author correctly notes that the diagnosis of UCS is often made through observation of posture and movement patterns. Janda did not advocate manual muscle testing because of the limitations of pain and reliability. The subjects in this study were included based on postural observation and pain complaints, rather than an actual diagnosis of UCS from a set of diagnostic criteria:

“Inclusion criteria for this group were: presence of postural deficiencies such as forward head posture, increased cervical lordosis and thoracic kyphosis, elevated and protracted shoulders, and rotation or abduction and winging of the scapulae, and constant or frequently occurring neck- and shoulder pain for more than 6 months”

This thesis helped validate the patterns of muscle imbalance with objective measurements of strength and range of motion. Other studies on patients with upper quarter musculoskeletal pain such as chronic neck pain (Jull et al. 1999), cervicogenic headache (Page, 2011), and shoulder impingement (Cools et al. 2003) have identified muscular strength imbalances consistent with Janda’s classification. While this study helped support Janda’s classification of muscle imbalance patterns in patients with symptoms of UCS, further research can help strengthen evidence-led clinical management. Evaluation the strength of the scapular muscles (also included in Janda’s muscle classification of UCS) would be beneficial. Unfortunately, this research did not correlate the objective findings of muscle strength and range of motion with Janda’s movement patterns (cervical flexion, shoulder abduction), which are critical to an appropriate diagnosis of UCS. I’m hopeful that the author considers publication in a peer-reviewed journal to help strengthen its validity in the rehabilitation literature.