Fascia. The tensional network of the human body. Edited by Robert Schleip et al.

Fascia. The tensional network of the human body. Edited by Robert Schleip et al.

Lead editor, Dr. Robert Schleip is a fascial researcher in Germany at Ulm University. Dr. Schleip and is co-editors Thomas Findley (USA), Leon Chaitow (UK), and Peter Huijing (Netherlands) have presented a very international and interdisciplinary flavor in their 2012 text. It provides the scientific foundation, clinical application, and research directions in fascia. Divided into 8 parts, it is comprised of 68 chapters written by various authors. While that sounds like a lot, the chapters are very short and sweet…this does limit the amount of detail on some topics, but as we know, there is sometimes too little to write about in lieu of hands-on experience. The 8 sections are:

Anatomy of the fascial body. Many anatomy texts and gross antomy dissections have ignored the fascia. Now that we are starting to appreciate fascia’s importance, more anatomy is emerging. We typically think of fascia as superficial and deep, but authors suggest there are 4 distinct layers: Pennicular, Axial/Appendicular, Meningeal, and Visceral. Fascial anatomy of different parts of the body are described in detail such as the shoulder, lower limb, thoraco-lumbar spine, and cervical region.

Fascia as an organ of communication. One of the most fascinating things to me is the concept of fascia as a living, breathing tissue that communicates. We know that fascia contains nerve and blood supplies, but it also has fibroblasts and mechanoreceptors that can communicate. Fascial communication occurs body-wide and includes proprioception, nociception, and ‘interoception’. Interoception is thought to be a ‘sense of the physiological condition of the body’ provided in particular from visceral fascia.

Anterior Muscle Slings

Anterior Muscle Slings

Fascial force transmission. Muscle and fascia together can not only produce tension, but can disperse and transmit force. This is an important aspect of functional movement patterns. One of the most important and less appreciated functions of the myofascial system is it’s ability to absorb shock and dampen stress on other tissues. Muscle Slings, Anatomy Trains, and Biotensegrity concepts are presented in this section, along with osteopathic approaches to movement.

Physiology of fascial tissue. Fascia is “alive”, thus, we need to remember how fascia maintains and heals itself. By discussing the process of healing, the role of the extracelluar matrix and how myofibroblasts work, the authors shed more light on this fascinating tissue. Furthermore, there is an interesting chapter on the interaction between fascia and the autonomic nervous system.

Fascia related disorders. This section was not as helpful as I would have hoped. I liked the section on hypermobility, because many forget that hypermobility is a fascial disorder and needs special consideration in rehab. I was not sure why the editors chose the specific disorders including frozen shoulder as a fascia-related disorder. Certainly, the argument can be made that joint capsules are a type of fascia, but I believe true fascial interventions (superficial and deep layers) play a minor role in frozen shoulder. This section was not well-organized, and I would have preferred they do a better job in identifying true fascia-related disorders perhaps by body part.

Diagnostic procedures for fascial elasticity. Again, this section was pretty ‘skimpy’ in my opinion, discussing fascial palpation and hypermobility (again). There’s simply not enough out there to help us with diagnosis; hence, the lack of support in research.

Graston Technique

Graston Technique

Fascia-oriented therapies. This section included many different fascial therapies including:

- Trigger point therapy

- Myofascial release

- Rolfing

- Instrument-assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization (Graston Technique, Gua Sha, etc)

- Osteopathic manipulation

- Fascial manipulation

- Microcurrent

With the variety of different fascial therapies, all with a limited amount of evidence-based efficacy, it’s sometimes difficult for clinicians and benefits to find appropriate and effective interventions.

Fascia research: methodological challenges and new directions. This final section really sums up the issues in diagnosing and treating fascial disorders. Ultrasound and MRI imaging, along with mechanical modeling, may help; but as the authors suggest, the interaction of clinicians and researchers is key. The Fascia Research Congress is one of the best ways this has been accomplished. I also recommend you purchase the proceedings of past Fascial Congress if you are interested.

In my opinion, the sections, ‘Fascia Related Disorders’ and ‘Diagnostic Procedures for Fascial Elasticity’ were the weakest sections of the text. Unfortunately, they should be the most clinically useful sections. The lack of research on fascial disorders and diagnostic procedures obviously has weakened this section of the text. However, as the authors state, “Knowledge will be developing continually” in the field.

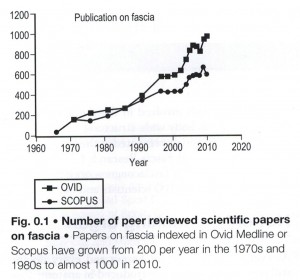

The beginning of the textbook points to the recent increase in fascial research articles in the graph below:

I believe the problem that we all run into as clinicians is the lack of hard evidence and the multitude of anecdotally-based treatments popularized in continuing education. I also believe we have a good handle on the basic structural foundation of fascia (anatomy, physiology, biomechanics) because they are easy to quantify. I understand the difficulties in applying a scientific method to a patient population, particularly one with myofascial disorders. However, our clinical skills can only improve as the science improves with better clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Therefore, as the editors so rightly stated, both researchers and clinicians need to “deviate from the preconceptions of each profession” to keep up with development in each others fields so knowledge can continue to develop.

Reviewed by Dr. Phil Page, September 2012

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

What about Naprapathic treatments? I have found the greatest amount of relief from going to a Naprapathic Doctor