Continuation: The Janda Approach: What’s the Evidence?

First and foremost, The Janda Approach is just that…an approach; a philosophy; a method; a concept. It’s NOT A TECHNIQUE! It’s much more difficult to quantify and measure a concept than it is a technique. As a method, the Janda Approach is a group of principles that guide evaluation and treatment that are based on scientific principles and human function. There’s no one technique within the Janda Approach that can be evaluated scientifically as you would evaluate a specific set of mobilization techniques for example. In comparison to the McKenzie method, for example, there are specific evaluation and exercise techniques that have been evaluated in the literature. However, Janda’s approach is more of a philosophy toward rehabilitation that’s based on what we know about the neuromusculoskeletal system and human movement.

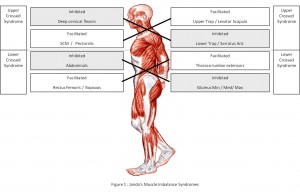

At this point, its important to define Janda’s approach to muscle imbalance. In contrast to a more structural viewpoint of dysfunction and muscle imbalance, Janda’s functional approach to muscle imbalance is based more on neurological function rather than biomechanical structure. It’s very easy to quantify a structural problem with the use of Xray, MRI and other tests; however, the challenge lies clinically in assessing and treating true ‘dysfunctions’ with no structural abnormality. This fundamental difference lies between Janda’s functional approach and Shirley Sahrmann’s biomechanical approach to muscle imbalance and movement dysfunction. Both are valid descriptions of muscle imbalance with different causes, which again supports the notion that even ‘muscle imbalance syndromes’ can be heterogeneous!

At this point, its important to define Janda’s approach to muscle imbalance. In contrast to a more structural viewpoint of dysfunction and muscle imbalance, Janda’s functional approach to muscle imbalance is based more on neurological function rather than biomechanical structure. It’s very easy to quantify a structural problem with the use of Xray, MRI and other tests; however, the challenge lies clinically in assessing and treating true ‘dysfunctions’ with no structural abnormality. This fundamental difference lies between Janda’s functional approach and Shirley Sahrmann’s biomechanical approach to muscle imbalance and movement dysfunction. Both are valid descriptions of muscle imbalance with different causes, which again supports the notion that even ‘muscle imbalance syndromes’ can be heterogeneous!

Shirley Sahrmann’s structural approach to abnormal movement has evaluation and treatment algorithms built into it that have been shown in a few studies to be valid and reliable. I would classify Sahrmann’s algorithm approach as more of a “system” rather than a “method” or “approach”. I know its semantics, but it’s important to understand that it’s always easier to validate a system compared to an approach.

Shirley Sahrmann’s structural approach to abnormal movement has evaluation and treatment algorithms built into it that have been shown in a few studies to be valid and reliable. I would classify Sahrmann’s algorithm approach as more of a “system” rather than a “method” or “approach”. I know its semantics, but it’s important to understand that it’s always easier to validate a system compared to an approach.

Janda’s approach is less rigorously structured, instead using a more flexible approach toward signs and symptoms to make a ‘functional diagnosis’. As with any clinical approach, Janda’s approach is yet another tool in our toolbox. It’s not an “end-all-be-all” approach, but it does provide clinicians with important insights to functional pathology. Janda often used ‘softer’ signs of dysfunction, since dysfunction is heterogeneous. His characteristic movement patterns were only ‘clues’ to the dysfunction and were put together as a cluster of signs and symptoms to establish the presence of his Crossed Syndromes. These softer signs such as postural abnormalities or abnormal movement patterns are often difficult to quantify across patients. By no means should a clinician consider a ‘positive prone leg extension’ to be a diagnosis of chronic low back pain, but it can help paint a picture of what might be going on from a motor control viewpoint.

This brings us to the discussion of Janda’s prone leg extension test, which he noted in early EMG studies has a specific firing order, and a characteristic dysfunctional firing order in chronic low back pain. Several studies have shown a specific firing order does not exist, which is not surprising given the heterogeneity of EMG measures. In practice, however, Janda noted that the specific order is difficult if not impossible to measure without EMG. Instead, he emphasized the faulty movement pattern associated with prone leg extension (and his other tests for that matter) as being early lumbar extension, rather than emphasizing the firing order. Unfortunately, many have mis-interpreted the clinical application of Janda’s research, resulting in controversy, especially around the so-called “Janda Sit-Up”.

Janda noted that the hip flexors were prone to tightness, while the abdominals were prone to weakness. One of his tests, the abdominal curl-up, helps identify this imbalance when the clinician places their hands under the heels of the patient. As the patient performs an abdominal curl-up, the heels should remain in contact with the clinician’s hands; if not, tight hip flexors may be causing the abnormal movement pattern. Others interpreted this to mean that contracting the hamstrings during an abdominal curl-up would reflexively inhibit the hip flexors, isolating the abdominals. Dr. Stu McGill of Canada clearly showed that the hip flexors cannot be inhibited during the abdominal curl up…and supported Janda’s contention that tight hip flexors can substitute for weak abdominals.

Janda noted that the hip flexors were prone to tightness, while the abdominals were prone to weakness. One of his tests, the abdominal curl-up, helps identify this imbalance when the clinician places their hands under the heels of the patient. As the patient performs an abdominal curl-up, the heels should remain in contact with the clinician’s hands; if not, tight hip flexors may be causing the abnormal movement pattern. Others interpreted this to mean that contracting the hamstrings during an abdominal curl-up would reflexively inhibit the hip flexors, isolating the abdominals. Dr. Stu McGill of Canada clearly showed that the hip flexors cannot be inhibited during the abdominal curl up…and supported Janda’s contention that tight hip flexors can substitute for weak abdominals.

Regarding chronic musculoskeletal pain, there remains much we don’t know as clinicians. We all have patients that just don’t get better…that we just don’t know what’s going on…that don’t make sense based on the literature. Yet, we are still held to the notion of ‘evidence’, when it’s clear that ‘evidence’ in itself isn’t always the answer. So, to claim that Janda’s approach isn’t valid because there are a few published studies is faulty reasoning. Even worse, based on the multitude of patients around the world who have benefited from Janda’s approach from clinicians who understand, identify, and treat his syndromes, it would be poor practice in my opinion to withhold treatments because it wasn’t published in a journal simply because clinical research hasn’t proven that something exists. Until “PROVEN NOT”, Janda’s approach has the biologic plausibility to be used clinically as a philosophy and not a technique.