Free excerpt from Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance: The Janda Approach

Janda’s Classification of Muscle Imbalance Patterns

Janda’s Classification of Muscle Imbalance Patterns

Through his observations of patients with neurological disorders and chronic musculoskeletal pain, Janda found that the typical muscle response to joint dysfunction is similar to the muscle patterns found in upper motor neuron lesions, concluding that muscle imbalances are controlled by the CNS (Janda 1987). Janda believed that muscle tightness or spasticity is predominant. Often, weakness from muscle imbalance results from reciprocal inhibition of the tight antagonist. The degree of tightness and weakness varies between individuals, but the pattern rarely does. These patterns lead to postural changes and joint dysfunction and degeneration.

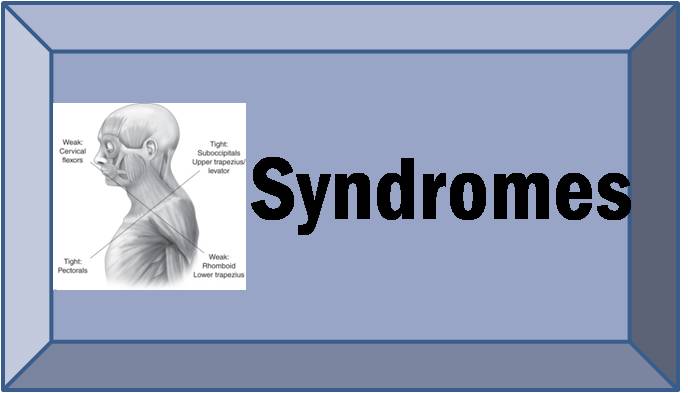

Janda identified three stereotypical patterns associated with distinct chronic pain syndromes: the upper-crossed, lower-crossed, and layer syndromes. These syndromes are characterized by specific patterns of muscle weakness and tightness that cross between the dorsal and the ventral sides of the body.

Upper-Crossed Syndrome

Upper-crossed syndrome (UCS) is also referred to as proximal or shoulder girdle crossed syndrome (figure 4.2a; Janda 1988). In UCS, tightness of the upper trapezius and levator scapula on the dorsal side crosses with tightness of the pectoralis major and minor. Weakness of the deep cervical flexors ventrally crosses with weakness of the middle and lower trapezius. This pattern of imbalance creates joint dysfunction, particularly at the atlanto-occipital joint, C4-C5 segment, cervicothoracic joint, glenohumeral joint, and T4-T5 segment. Janda noted that these focal areas of stress within the spine correspond to transitional zones in which neighboring vertebrae change in morphology. Specific postural changes are seen in UCS, including forward head posture, increased cervical lordosis and thoracic kyphosis, elevated and protracted shoulders, and rotation or abduction and winging of the scapulae (figure 4.2b). These postural changes decrease glenohumeral stability as the glenoid fossa becomes more vertical due to serratus anterior weakness leading to abduction, rotation, and winging of the scapulae. This loss of stability requires the levator scapula and upper trapezius to increase activation to maintain glenohumeral centration (Janda 1988).

Lower-Crossed Syndrome

Lower-crossed syndrome (LCS) is also referred to as distal or pelvic crossed syndrome (figure 4.3a; Janda 1987). In LCS, tightness of the thoracolumbar extensors on the dorsal side crosses with tightness of the iliopsoas and rectus femoris. Weakness of the deep abdominal muscles ventrally crosses with weakness of the gluteus maximus and medius. This pattern of imbalance creates joint dysfunction, particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 segments, SI joint, and hip joint. Specific postural changes seen in LCS include anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis, lateral lumbar shift, lateral leg rotation, and knee hyperextension. If the lordosis is deep and short, then imbalance is predominantly in the pelvic muscles; if the lordosis is shallow and extends into the thoracic area, then imbalance predominates in the trunk muscles (Janda 1987).

Janda identified two subtypes of LCS: A and B (see figure 4.3, b-c). Patients with LCS type A use more hip flexion and extension movement for mobility; their standing posture demonstrates an anterior pelvic tilt with slight hip flexion and knee flexion. These individuals compensate with a hyperlordosis limited to the lumbar spine and with a hyperkyphosis in the upper lumbar and thoracolumbar segments.